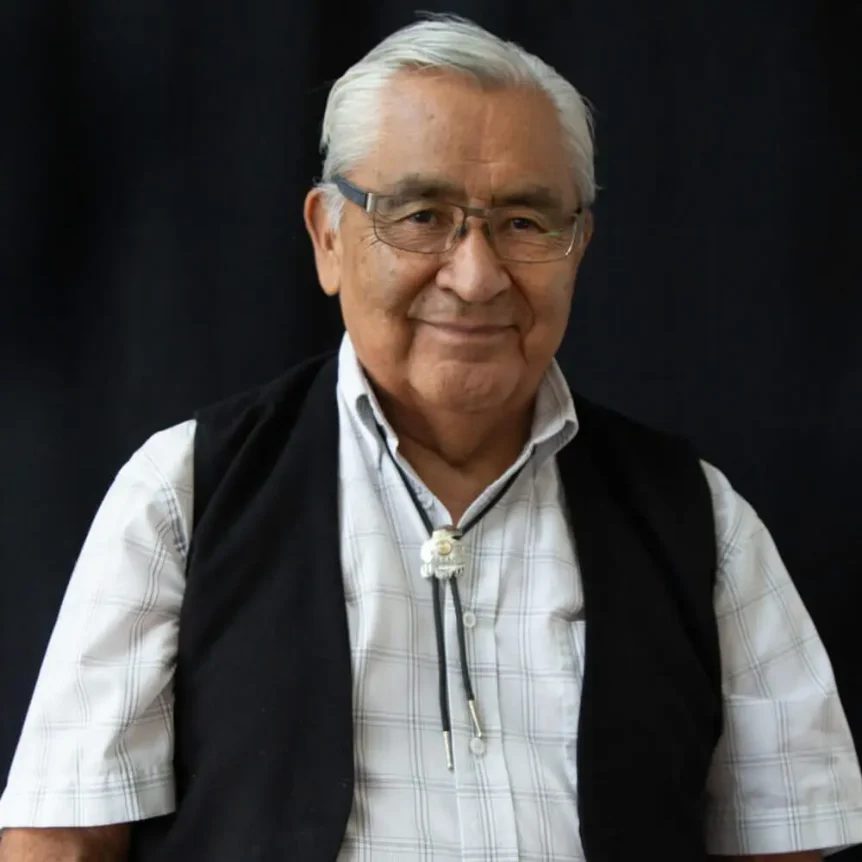

Allan is a member of the Heiltsuk First Nation from Waglisla, BC where he was raised learning about his culture, and learning about plant medicine from his mother. “Smudging was a ritual that was introduced to me at a very young age to protect and prevent spirits from latching on to us children,” says Allan. That connection to his culture came to an abrupt end when he was 13 years old was sent to Port Alberni Residential School.

He was determined to attend University and worked hard to be accepted into the University of British Columbia where he acquired a BA in Sociology, a BSW in Policy and Programs and a Masters in Social work in Community Development. It wasn’t until he graduated and went to Ottawa that he was exposed to Indigenous spirituality again.

He was the Head of the Native Offender Program with Correctional Services Canada and was instrumental in drafting the first Directive to allow Aboriginal Inmates in all federal institutions in Canada to use traditional methods and materials.

“It was during this process that my spiritual journey began in 1985,” says Allan. He eventually went on to be a PhD candidate at the University of Victoria, with an interest in studying Aboriginal Governance from the perspective of Indigenous teachings where traditional laws are entrenched in the oral teachings and Indigenous languages.

“I am spiritually inclined and a strong supporter of traditional ceremonies and rituals,” says Allan. He participated in sweat lodge ceremonies, pipe ceremonies and talking circles. In 2003 he completed a four-year Sundancer ceremony with Dave Blacksmith in Winnipeg, Manitoba. “My most rewarding experience was as a helper for Dave when he performed his healing ceremony on individuals infected by cancer, which spanned over four years,” says Allan.

Allan is married to Shirley who is of Gitxsan ancestry and they have three children, one who is adopted from the Cree Nation in Saddle Lake, Alberta. He likes being an Elder because he enjoys the process of ensuring the best care and safety of children and families. His advice for staff is to be empathetic and understanding to the needs of the Indigenous child, youth and family. He also believes that culture is crucial. “Having a sense of abandonment and not belonging is a terrible burden to have to bear, so knowing who you are and where you are from is very important,” says Allan.

“I approach my role with an open heart and open mind and share my love and caring with everyone that is involved with every phase of the child welfare process,” says Allan.